South Sudan gained its independence on July 9, 2011, but it took another 10 days before its border with Sudan made a debut in Google Earth. Wikipedia, OpenStreetMap and even this blog made that border available from day one. So what would justify the delay at Google?

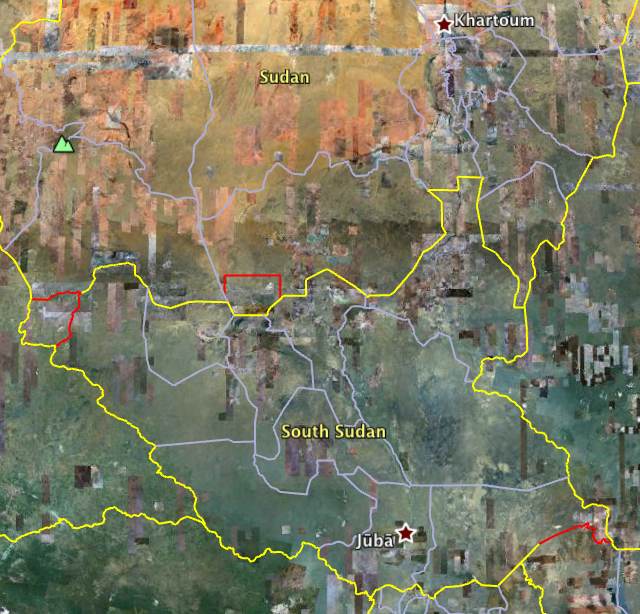

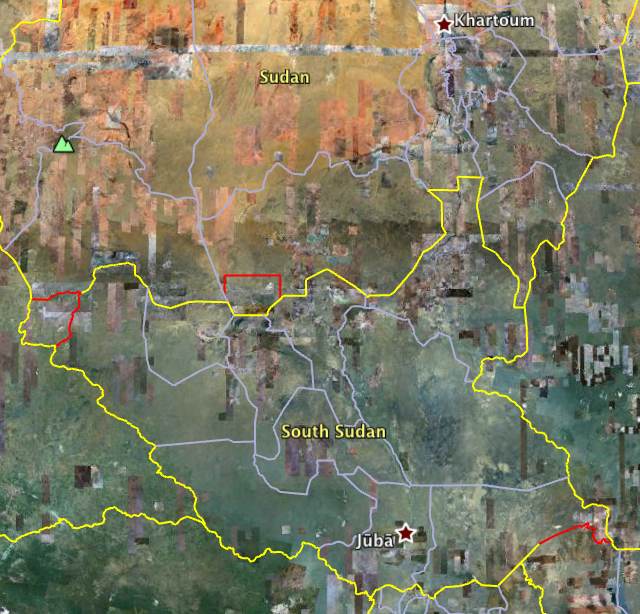

The answer is hinted at if you compare Google’s version of the border with the dataset most others used. They are not the same. Conspicuously, Google outlines two large areas — Abyei in the center and the Kafia Kingi enclave to the west — in red, indicating a dispute; but there are also more subtle discrepancies between the two delineations of the border along the entire course. (Just open this file in Google Earth to see the differences.)

After decades of civil war, the world’s newest border is also one of the most volatile. Straddling it are mineral deposits, oil reserves and traditional grazing rights, all of which intermittently lead to clashes that could easily escalate. Delineating an accurate and authoritative version of this border is thus a crucial step to a stable peace.

Google’s map data carries no authority in any legal sense, not any more than Microsoft’s, Yahoo’s or National Geographic’s, but that is not surprising. What sets it apart from the others, however, is that over the past half decade, the ubiquitous use of Google Earth as a universal digital atlas has bequeathed it a popular authority, and a sense that Google’s choice regarding a border (or place name) constitutes a weighty endorsement in the court of global opinion. This has led to remarkable situations where states themselves have petitioned Google about perceived bias or errors in its maps. Documented cases include Cambodia, Iran, Azerbaijan and even Japan. In an even more bizarre case, Nicaragua’s government cynically invoked Google Earth’s (erroneous) depiction of its border with Costa Rica to justify a land grab.

How Google depicts South Sudan’s northern border, then, matters. And so it has done its homework. This post will get into the nitty-gritty in a minute, but if you want the executive summary, here it is, based on the story I got from Google: Google was late because it decided to use a brand new and detailed delineation of the border made by the Geographic Information Unit at the US State Department, which late in the game needed some more information about the disputed borders. Google in turn needed time to decide how to apply its policy for disputed borders and names to the specific instance of South Sudan. Hence the delay.

But why prefer the State Department/Google version over the one already in the public domain, derived from colonial-era surveys of Sudan’s provincial boundaries? Which is the most accurate?

The answer to this requires a brief but fascinating detour into an explanation of the difference between the delimitation, delineation and demarcation of a boundary. The delimitation of a boundary is its definition, for example as a text in a treaty or judgment, and it often comes accompanied by maps delineating the boundary. But a delineation on a map can also be made much later, based on interpretations of delimitations in historical documents that may be ambiguous. Demarcation, in turn, is the physical marking of a boundary on the ground, through fences, beacons, signs, etc. Sometimes boundary definitions can reference existing physical boundary markers, so the process is not always linear. Ideally, the text, map, and ground markers agree without ambiguity. In the case of South Sudan’s border with Sudan, there are discrepancies large enough to fit a small town, as we’ll see.

In reading up on South Sudan these past few weeks, I found some great literature on the specifics of the North-South border, via the wonderfully thorough and focused blog South Sudan Info, which recently came up with a reading list specifically about the border. Some reports on the list look at all the potential flash points along the border, and here it is evident that Abyei and Kafia Kingi enclave are merely the two most preëminent of up to nine contested boundary areas, depending on who’s counting.

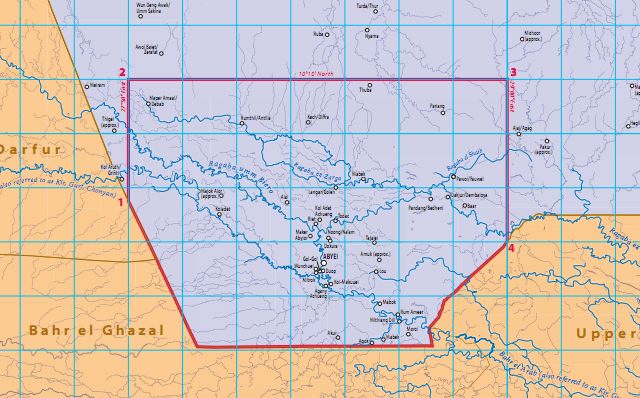

Most of these boundary issues are matters of delineation and demarcation rather than delimitation — where there is agreement about the definition of the border, but not about where exactly it runs. Here’s one example, excerpted from When Boundaries Become Borders — The impact of boundary-making in Souther Sudan’s frontier zones (PDF, 2010), by Douglas H. Johnson:

The delicacy of determining the north-south boundary is well-illustrated by Upper Nile state’s northernmost boundary with White Nile State. This straight line runs west to east and would appear to be unproblematic and a simple matter to confirm. Unfortunately, this is not the case. The northwestern corner of this boundary (where it meets South Kordofan) is supposed to be anchored on Jebel Megeinis [hill], but modern GPS readings have revealed that Jebel Megeinis is not located on the coordinates that have been recorded on the Sudan Survey maps since the early part of the 20th century. Not only that, but there are two beacons on the mountain, one at the base, and one at the summit. A precise fixture thus turns out to be imprecise, creating room for argument.

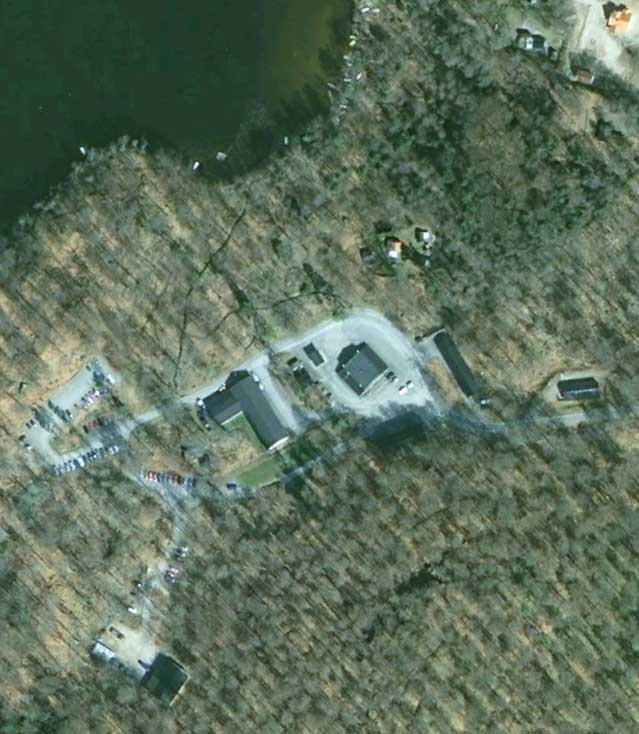

I’ve marked that location on Google Earth, where you can see that US State/Google’s brand new delineation places the corner atop Jebel Megeinis hill, as called for by the original delimitation. At the foot of the hill lies a small town, Al Miqenis.

Here’s how the US State Department comments on its delineation of that section of the border, from a draft of its “Detailed Boundary Recovery Report”, as provided by Google:

[…] The line is much more accurate near where it is anchored by the distinct Jebel Megeinis peak. This is fortunate, as the last two km of this line [coming from the southeast] (minus the last half km on the peak’s steep slopes) cuts through by far the most heavily built-up area near the entire 1956 line [dividing north from south], the town of Al Miqenis… at least 20 buildings and many more small lots are literally sliced by the line. This town does not appear on either the 1930’s Sudan Survey map, [nor] the 1970’s Soviet map (though a major road intersection does appear).

From Jebel Megeinis, the line follows the parallel defined by that peak’s distinct summit due east for 71 km and is thus one of the entire line’s few absolutely accurate sections.

In the dataset used by Wikipedia, OSM and others, most of the town of Al Miqenis is located in Sudan (i.e. outside the green area in the image above.) In Google Earth, it lies mainly in South Sudan (i.e south and east of the yellow line.) Of course, in the Wikipedia/OSM dataset the corner was never intended to be located to the southeast of the town, but on top of Jebel Megeinis hill; it’s just that the hill turns out not to be where previous mappers thought it was, through inaccurate surveying. This kind of error would have been cemented when paper reference maps were replaced by digital datasets, but politicians may not necessarily be swayed by such explanations when a border town is up for grabs.

For Abyei and the Kafia Kingi enclave, the dispute is not a question of delineation or demarcation but of delimitation, and these are the ones that Google has drawn in red.

At this point, there is no way to avoid a quick history lesson. From 1898, Sudan was jointly governed by the British and the Egyptians (a so-called condominium), but with northern and southern Sudan firmly separated into different regions — the northern provinces tied to the Arab sphere of influence, the southern provinces connected to Britain’s East African colonies, where Christian missionaries were given free rein. By the 1920s, crossing between these two territories required a passport, and Britain was planning two very different futures for them. But it was not to be: After WWII, a stressed UK decided on central administration from Khartoum, and it was thus that in 1956 a single unified Sudan became independent.

After decades of civil war between northern and southern Sudan, in 2005 the government of Sudan and the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) agreed on a process for the eventual secession of South Sudan. The Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) defined the future international border to be the boundary between Sudan’s northern and southern provinces at independence in 1956.

Abyei, which lies to the north of the 1956 boundary, is subject to a separate protocol: It is populated predominantly by ethnicities affiliated with South Sudan, and so Khartoum was coaxed by the international community into allowing Abyei’s inhabitants to decide whether they too want to join South Sudan. Pending a delayed referendum amid signs the government of Sudan is increasingly unwilling to part with Abyei, the protocol nevertheless dictates that the area is to be governed jointly by Sudan and South Sudan until the people have made a choice. In other words, Abyei is in limbo, and that is reason enough to color it red on Google Earth.

What about the Kafia Kingi enclave? I defer to Edward Thomas, who wrote an entire book (PDF, 2010) on this remote and sparsely inhabited region of Africa, long used as slave hunting grounds by Arab slave traders. Kafia Kingi was part of southern Sudan at independence in 1956, but in 1960 jurisdiction over the area was transferred to northern Sudan.

The 2005 peace agreement dictates that Kafia Kingi should therefore be returned to southern rule upon independence for South Sudan. On the ground that transfer does not seem to have happened, however. Even if the agreement is clear on the delimitation of the boundary, a de facto continued occupation and administration by Sudan is reason enough to color the boundaries red.

Because the Wikipedia/OSM border dataset is based on Sudan’s provincial boundaries as they existed in 2011, not in 1956, they do not show Kafia Kingi as part of South Sudan — it stays with Sudan’s province of South Darfur. This is an error. You could even argue that South Sudan’s claim to Kafia Kingi is stronger that that for Abyei, because Kafia Kingi belonged to southern Sudan in 1956 and thus its transfer requires no further discussion. This view is apparently held by the CIA; its World Fact Book entry depicts Abyei as disputed but Kafia Kingi as integral to South Sudan:

On the other hand, it is not clear whether South Sudan is actively pursuing a claim on Kafia Kingi. The fledgling state has a lot on its plate, and cannot afford to confront Sudan militarily. Official maps of South Sudan are hard to come by: The only map available on the government’s official website omits both Abyei and Kafia Kingi, though likely for the same reason it is missing from the dataset used by Wikipedia and OSM. For the International Court of Justice or other arbitration courts, however, such omissions will over time come to undermine territorial claims. Edward Thomas, meanwhile, in his book suggests that Khartoum is holding on to Kafia Kingi as a bargaining chip, because its sparse population and mineral wealth makes it easily tradable for concessions elsewhere along the border.

In other words, I can see a scenario where Khartoum would offer to finally let Abyei go in return for Kafia Kingi. South Sudan would then have to consider whether it could get more through other means, and at what price, or else accept a somewhat ignoble trade.

(As of this writing Bing Maps and Yahoo Maps still show Sudan and South Sudan as one nation indivisible.)

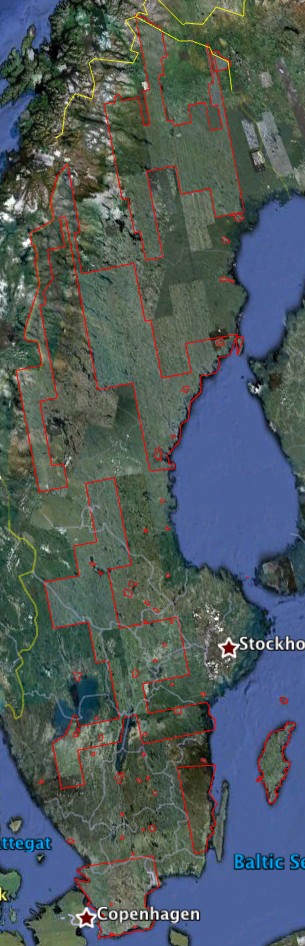

Just a quick heads up for Swedes and/or power users of Google Earth: I noticed via the

Just a quick heads up for Swedes and/or power users of Google Earth: I noticed via the