In 2008, mainstream camera manufacturers began introducing models with built-in GPS receivers, to automatically add location metadata to photographs. Since then, 10 brands have released a total of 41 distinct models of GPS-enabled cameras. You can find most of them in DPReview’s filterable database.

When the GPS-capable Panasonic Lumix TS4 launched in early 2012, GPS Tracklog’s Rich Owings noticed a strange footnote in the press release:

GPS may not work in China or in the border regions of countries neighboring China.

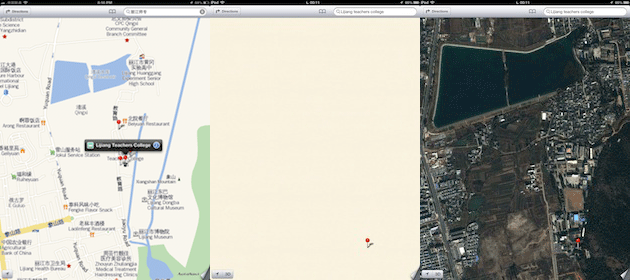

Rich and I pondered aloud on Twitter as to how in-camera GPS receivers could possibly break when used in China. There is nothing wrong with GPS in China, as anyone who has successfully flown there can attest. Tens of millions of Chinese-bought iPhones have access to highly accurate latitude and longitude readings via Apple’s default compass app, which uses assisted GPS. (I just had a friend in Shanghai read me her coordinates over Skype and confirmed her position in Google Earth.) So why would Panasonic choose to hobble its GPS-enabled cameras so that the location data is withheld from users whenever that location is deemed by the firmware to be in China?

One mooted reason was a Chinese law prohibiting mapmaking and surveying without a license. Foreigners logging location coordinates via GPS while travelling near sensitive sites have been detained on these grounds. In 2010, Chinese authorities cracked down on user-generated mapping, aka neogeography, citing security risks. And in a continuing sign of this trend, just last week a prominent Chinese state TV anchor used his microblog to rail against “foreign spies who find a Chinese girl to shack up with while they make a living compiling intelligence reports, posing as tourists in order to do mapping surveys and improve GPS data for Japan, South Korea, the United States and Europe.”

A tweeted response from Panasonic PR confirmed a legal motivation for the technical restriction:

Despite follow-up questions no more information was forthcoming, beyond the suggestion that we check the manual for details.

This left many questions unanswered. Why would a Japanese manufacturer selling a camera in the US and Europe be so eager to ensure that its customers obey a (dubious) Chinese law? What is a Lumix TS4 owner supposed to do if she receives permission to log GPS coordinates in China? What happens if the law changes so that permission is no longer required? How did Panasonic end up second-guessing what customers should or should not do in China?

One possibility is that Panasonic believes its customers would sue if they got arrested for inadvertently logging location data while travelling around China. But then why not allow a manual override for informed and/or authorized users?

Perhaps Panasonic fears a near-future dystopian scenario where GPS-enabled cameras are confiscated by Chinese border guards if they are at all able to log data inside China. But surely, with an average product life-cycle of one year, that’s not a big risk?

Maybe Panasonic decided it would be too expensive to release both a China-compliant model and an unmolested global model — and so decided to just release the China-compliant model globally, having taken note of the size and growth of the Chinese consumer camera market.

Or maybe the GPS chip in the camera is manufactured in China, and thus needs to meet some kind of Chinese security restriction before it gets an export license. Admittedly, my scenarios are getting somewhat farfetched.

In the absence of good answers, I let the story languish a few months, hoping to find someone in the camera or GNSS industry able to confirm both the why and the how of the Lumix TS4’s curious behavior when inside China.

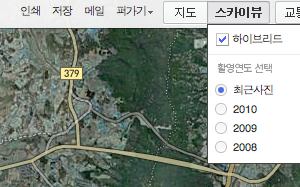

Unable to get any more clarity on the matter, I recently decided to check the manuals of all 41 models across all 10 mainstream brands, to see if others besides Panasonic admit to interfering with the GPS function of their cameras for political reasons. It turns out that five of the 10 brands do.

Panasonic, Leica and FujiFilm prevent their cameras from displaying location information when in China. Nikon and Samsung appear to restrict location information in some other way. Sony, Canon, Pentax, Casio and Olympus do not interfere with the GPS function of their cameras when in China (or at the very least do not admit to it in their manuals).

Here’s the assembled evidence — relevant excerpts from all the manuals of all the GPS-enabled cameras sold since 2008. First, the culprits:

Panasonic:

Lumix DMC-ZS7 (Jan 2010)

Lumix DMC-ZS10 (Jan 2011)

Lumix DMC-TS3 (Jan 2011)

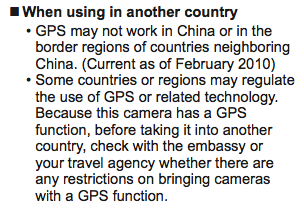

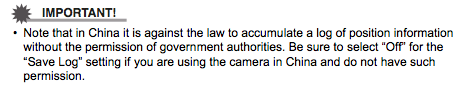

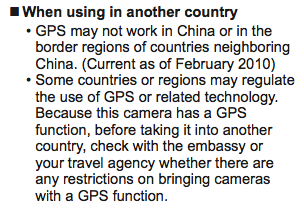

All these cameras’ manuals have an explanation like this:

Surprise: All three of Panasonic’s GPS-capable predecessors to the Lumix TS4 cripple GPS use inside China, ever since 2010. We only noticed in 2012 because the TS4 press release mentioned it (and no, I don’t have a habit of reading manuals of cameras I don’t own:-).

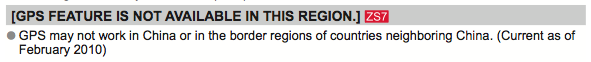

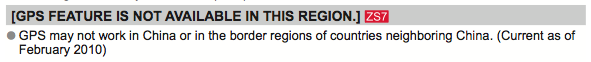

In addition, all three cameras have a ready-made error message for when the camera has decided to conceal its location: “GPS FEATURE IS NOT AVAILABLE IN THIS REGION.”

Lumix DMC-TS4 (Jan 2012)

The manual for the TS4 is not yet available on the web, but the official website makes clear about what happens to these cameras when in China:

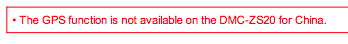

Lumix DMC-ZS20 (Jan 2012)

Same goes for this camera:

Leica:

Because Leica’s V-Lux cameras are rebranded Panasonic Lumixes, we get an opportunity to see how two different marketing departments describe the same technical limitation. Leica, it turns out, is far more articulate about how and why their cameras are crippled:

V-Lux 20 (Apr 2010) (a rebranded Lumix ZS7)

This in addition to the same error messages as on the Lumix ZS7. (So much for Panasonic trying to be coy in its manuals.)

V-Lux 30 (May 2011) (a rebranded Lumix ZS10)

V-Lux 40 (May 2012) (a rebranded Lumix ZS20)

The V-Lux 40’s manual is identical to that of the older Lumix ZS7 and ZS10 when it comes to describing GPS limitations (see above).

FujiFilm:

FinePix F550 EXR (Jan 2011)

FinePix XP30 (Jan 2011)

FinePix F600 EXR (Aug 2011)

FinePix F770 EXR (Jan 2012)

FinePix XP150 (Jan 2012)

All FinePix cameras carry this disclaimer:

Nikon:

Nikon seems schizophrenic about its approach to GPS:

Coolpix P6000 (Aug 2008)

One of the very first compacts on the market to have built-in GPS, this camera’s manual makes no mention of GPS restrictions or China. This is how it should be. Nikon’s GP-1 GPS unit for its DSLRs also makes no mention of restrictions.

Coolpix AW100 (Aug 2011)

Coolpix S9300 (Feb 2012)

Coolpix P510 (Feb 2012)

By 2011, however, Nikon’s cameras warn that “GPS may not function properly” in and around China:

On a Nikon website, A user shares his experience using GPS with his Coolpix AW100 in China:

The GPS in my Lumix [TZ10] camera is disabled when in China. The camera gives an information message that it disables the GPS while in China. I was pleasantly surprised that Nikon [Coolpix AW100] does not disable the GPS in China but places some limitations on its use. The locations using the GPS in China seem to be off by about 500 ft to the west. In addition, the map function does not work in China and there are not location points for China in the database. I found it interesting that while I was in Southern China, several miles from Hong Kong, the camera would like the closest location point in Hong Kong (which turned out to be a KCR metro station about 10km away. I am very glad the GPS works in China even with these limitations.

Samsung:

Samsung’s manuals, alas, border on the unintelligible. They are obviously transcribed from some other language:

ST1000 (Aug 2009)

HZ35W (Jan 2010)

It is not clear at all where the GPS works, nor does it make any sense to only allow cameras purchased in China to receive GPS signals in China.

Discussing the GPS performance of the Samsung HZ35W may be academic, however — DPReview’s review says that the camera’s GPS function is “idiosyncratic at best, and at worst, non-functional”, with many users not being able to get it to work at all. (Maybe because it appears to work only in a minority of countries, as per the manual.) Meanwhile, Samsung has not come out with updates to its GPS cameras for over two years.

Next up, those manufacturers who do not second-guess their customers:

Sony:

Cyber-shot HX5 (Jan 2010)

SLT-A55 (Aug 2010)

Cyber-shot DSC-HX7V (Jan 2011)

Cyber-shot DSC-TX100V (Jan 2011)

Cyber-shot DSC-HX100V (Feb 2011)

Cyber-shot DSC-HX9V (Feb 2011)

SLT-A65 (Aug 2011)

SLT-A77 (Aug 2011)

Cyber-shot DSC-TX200V (Jan 2012)

Cyber-shot DSC-HX200V (Feb 2012)

Cyber-shot DSC-HX10V (Feb 2012)

Cyber-shot DSC-HX20V (Feb 2012)

Cyber-shot DSC-HX30V (Feb 2012)

None of these camera manuals reference China in any way. All manuals carry the exact same text:

Canon:

PowerShot SX230 HS (Feb 2011)

PowerShot S100 (Sep 2011)

PowerShot SX260 HS (Feb 2012)

PowerShot D20 (Feb 2012)

None of these camera manuals reference China in any way. All manuals carry a version of this text:

Additionally, Canon gets points for reminding users of potential privacy issues when geotagging photos.

Pentax:

Optio WG-1 GPS (Feb 2011)

Optio WG-2 GPS (Feb 2012)

The GPS utilities guide for these cameras carries an identical short reference:

Casio:

Exilim EX-H20G (Sep 2010)

The EX-H20G’s manual is perhaps the most straightforward of all:

Olympus:

Tough TG-810 (Mar 2011)

Tough TG-1 iHS (May 2012)

The manual is not up on the web yet, but the camera’s web page makes no mention of China or restrictions, and there is no reason to suspect a policy change since the TG-810.

Implications

Why does all this matter? Wherever local laws prohibit the sale or use of a personal electronics device able to perform a certain function, manufacturers have traditionally chosen not to sell the offending device in that particular jurisdiction, or — if the market is tempting enough — to sell a crippled model made especially for that jurisdiction.

For example, Nokia chose not to sell the N95 phone in Egypt when the sale of GPS-enabled devices there was illegal before 2009, whereas Apple opted to make and sell a special GPS-less iPhone 3G for that market. Early models of the Chinese iPhone 3GS lacked wifi, while the Chinese iPhone 4/4S has firmware restrictions on its Google Maps app.

The risk to consumers in freer countries is that personal electronics brands might be tempted to simplify their manufacturing processes by building just one device for the global market, catering to the lowest common denominator of freedom — especially if the more restrictive legal jurisdictions contain some of the most attractive markets, such as mainland China.

Still, in the absence of more information from Panasonic, Leica, FujiFilm, Nikon and Samsung, I can’t decisively say whether this is the business logic behind their decision to cripple the GPS in their cameras. And yet uncrippled GPS cameras from Sony and others are freely available for sale in China, for example on Taobao, China’s eBay:

And Sony’s official mainland China site is more than happy to offer instructions in Chinese on how to use the GPS function.

Consumers in the market for a GPS-enabled camera should be informed that five of the mainstream brands engage in location-based censorship. Choose another brand, or get a dedicated handheld GPS device to sync tracklogs with your camera — I don’t suspect Garmin or Magellan will stop working in China anytime soon.