UPDATE: Scroll to the end of the article to see the final confirmed location of the compound.

UPDATE 2: A new post: 2011 DigitalGlobe imagery of Bin Laden compound, now on Google Earth

UPDATE 3: More posts: GeoEye publishes post-raid satellite image of Bin Laden compound, In the Situation Room, aerial imagery of the Bin Laden compound.

Osama Bin Laden’s death first manifested itself as short news items on Pakistani news sites: “Copter crashes on Kakul road – Monitoring Desk“, and indeed, later we would hear that one of the helicopters used in the raid on Bin Laden’s compound was damaged and destroyed.

The repercussions of Bin Laden’s death are still uncertain, but this post will just concern itself with the location of this compound. Where exactly was it? Can we find it on Google Earth?

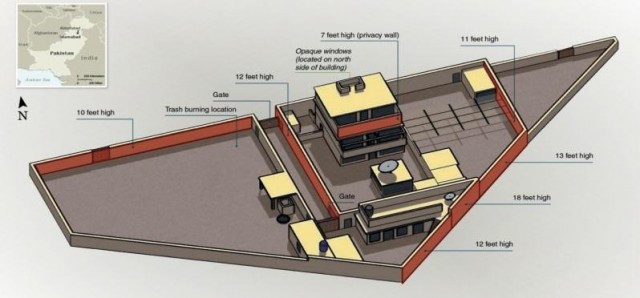

Al Jazeera English mentions “a mansion” surrounded by high walls, comprised of “boxes” with no windows. On a map of Abbottabad shown on their screen, Al Jazeera shows Kakul Road, and marks a specific location on that road, at the edge of some fields.

In a news story sourced to CBS/Associated Press, we get an eyewitness to tell us the following:

“I heard a thundering sound, followed by heavy firing. Then firing suddenly stopped. Then more thundering, then a big blast,” he said. “In the morning when we went out to see what happened, some helicopter wreckage was lying in an open field.”

He said the house was 100 yards away from the gate of the academy.

The New York Times reports that the mansion was “on the outskirts of the town’s center, set on an imposing hilltop and ringed by 12-foot-high concrete walls topped with barbed wire.” It goes on:

The property was valued at $1 million, but it had neither a telephone nor an Internet connection. Its residents were so concerned about security that they burned their trash rather putting it on the street for collection like their neighbors.

American officials believed that the compound, built in 2005, was designed for the specific purpose of hiding Bin Laden.

Is it possible to correlate these disparate clues? Not really. The NYT is most likely to be wrong as to the location — Al Jazeera footage shows a backdrop of flat fields near the compound, not a hilltop. Also, from the position marked by Al Jazeera on the map, the front gate of the military academy is around 2km away along the straight Kakul road, rather than the “100 meters” mentioned by the AP eyewitness.

I am inclined to give Al Jazeera the benefit of the doubt on this. They are the most likely to have people on the ground with the correct information, they are specific in their pinpointing of the location and their video footage supports their map.

But there is one further clue we can use. Google Earth’s high-resolution map of the area has imagery from June 15, 2005 — almost 6 years old. One set of older imagery is available — from March 23, 2001. If the NYT sources are correct on Bin Laden’s mansion being under construction in 2005 (and on this they are likely to be correct, as it sounds like a piece of information from an intelligence source) then we should be able to compare the 2001 imagery with the 2005 imagery, and look for any mansion-sized construction going on in 2005.

[Update May 3: Google today updated its base image layer to include imagery from Abbottabad taken on May 9, 2010 — just under a year ago. You can still see the imagery from 2005 (and 2001) by using the historical imagery time slider tool in Google Earth.]

And Indeed, in the specific region marked by Al Jazeera, there is construction underway in 2005. Below is the imagery in 2005, then in 2001, then in 2005 again with the construction marked.

Imagery taken on June 15, 2005

Imagery taken on March 23, 2001

Construction ongoing on June 15, 2005

Of course, it is possible that construction on the mansion began after June 15, 2005.

Finally, here is a Google Map I’ve made of the locations mentioned in this article:

View Osama Bin Laden’s mansion location.kmz in a larger map

And here it is as a downloadable KML file for Google Earth.

It’s possible that these locations are wrong. The easiest way to find the precise place would be to walk on over there and take a look, but failing that, I will keep this article updated with more accurate information as it becomes available.

UPDATE 9:53 UTC: Pakistan-based journalist Omar Waraich tweets that the location of the mansion, and where he is headed to, is Bilal colony/town in Abbottabad. On Google Maps there is a marker tagged “Bilal Mosque” which corresponds perfectly with the screenshots of Google Earth above. In other words, there is reason to be more confident that the above locations are correct.

UPDATE 13:29 UTC: Here are screen grabs from Al Jazeera of the compound:

As you can see from the wide shot, the compound (not so much a “mansion” in terms of opulence”) faces the edge of an area with fields. Zooming in, we can see a section of red tarpaulin erected to hide ongoing investigatory activity. The mountainscape behind the compound can be reconstructed in Google Earth from the Bilal Town location pinpointed above. In other words, this is more evidence that Bin Laden’s compound is in the above location, most likely on the dirt road that runs along the creek visible in the Google Earth screenshots.

UPDATE 13:51 UTC: Here’s a screengrab of Al Jazeera’s map referred to above (via):

UPDATE 14:52 UTC: After a comment left by Dave (below), I took another look further to the west east of Bilal Mosque to see if there was any prominent construction there in 2005, in an area that is less built up than in Bilal Town proper. And indeed, there is one conspicuous compound that sticks out, and which closely matches the video imagery above. Here is the view in Google Earth in 2001:

And here it is in 2005:

I think we have a very likely candidate here. (I’ve updated the map and added the location to the Google Earth KML file.)

UPDATE 15:13 UTC: Published a few minutes ago, this new story by the BBC all but confirms that this compound is indeed the correct location, with a highly detailed map:

Thank you for playing everyone. We have a winner:

View Osama Bin Laden’s mansion location.kmz in a larger map

UPDATE 16:22 UTC: The CIA Pentagon releases aerial imagery confirming that this is indeed the location, as reported by the National Journal: (Click to enlarge. PDF of originals)