- Afghanistan I: The Wall Street Journal reports on how US forces in Afghanistan are ramping up the use of airdrops to provision troops in the field, so as to minimize the use of IED-infested roads:

The air crews prepare for each mission by studying a three-dimensional Google Earth image of the line of approach, giving them a moving, cockpit-window view of the ridges, rivers and villages they’ll see as they near the drop zone.

I wonder if the US military uses Google’s publicly available imagery dataset, or if they use Google Earth Enterprise and roll their own — because the publicly available imagery is at least 7 years old, and Afghanistan is conspicuously absent from the now semi-monthly updates.

- Barrier islands: Researchers studying barrier islands have found that Google Earth’s imagery, especially if only a few months or years old, is much more accurate than the official maps and databases that are meant to keep track of them. They’ve now taken to scouring Google Earth’s publicly available dataset to “discover” over 600 such islands:

“Basically nothing beats Google Earth for getting the whole story. Google Earth has opened up a whole new world for those who study physiography of the globe,” Pilkey said.

Just as with people looking for archaeological discoveries or meteorite craters, the economics of free is compelling. It costs nothing to check unlikely places, which would never have been accessible when satellite imagery cost thousands of dollars to commission. As a result, the researchers discovered the world’s longest chain of barrier islands, off Brazil’s northeast coast, where they thought the tidal differences prevented such islands from forming.

- Afghanistan II: This week, photojournalist and filmmaker Tim Hetherington was killed in Misrata will covering the conflict there. A few months ago I saw his much-acclaimed war documentary RESTREPO, about US troops setting up a remote forward base on a valley spur in Nuristan, surrounded by insurgents. Hetherington and fellow filmmaker Sebastian Junger embedded themselves with the soldiers over the course of a year in 2007. It’s a strong, compelling film.

The documentary often refers to local place names and shows the maps used by soldiers, while the panoramic shots are distinctive enough that I thought it might be possible to identify exactly where the base was in Google Earth. Others on Google Earth Community had already beaten me to it. The precise location of Korengal Outpost (the main camp) is here, while OP Restrepo, the forward base, is here. Google Earth’s imagery is from 2004 and not of the highest resolution, but the digital elevation model is quite detailed, and provides very useful context when watching the film — which I highly recommend. (It’s available on Netflix)

- Thailand-Cambodia border conflict: As you may have read, yet another temple on the Thai-Cambodian border is cause for a deadly military escalation. Called “Prasat Ta Khwai” or “Ta Krabey”, the temple straddles the spur that defines much of border between these two countries, and lies about 140 kilometers to the west of the much better-known Preah Vihear temple, which is the disputed site most often in the headlines these past few years. This temple is almost completely obscured by jungle coverage, but the link above and Geonames both triangulate to the correct place:

View Larger Map

Yearly Archives: 2011

links for 2011-03-31

-

"Images from Google Earth show a sharp contract between forest cover in Sarawak, a state in Malaysian Borneo, and the neighboring countries of Brunei and Indonesia at a time when Sarawak's Chief Minister Pehin Sri Abdul Taib Mahmud is claiming that 70 percent of Sarawak's forest cover is intact."

Freya Stark’s excursion in Afghanistan circa 1968 — mapped

At the very top of my to-do list for travel destinations lies Afghanistan, but over 30 years of war there have made it hard to justify visiting in the pursuit of pleasure. So I get my fix vicariously — most recently in London, where the British Museum is hosting a traveling exhibition with treasure from the National Museum of Afghanistan in Kabul. (It previously traveled around the US.) The curators have focused on material from four different archeological sites, each with a distinct cultural identity — Tepe Fullol’s gold bowls from the third millenium BCE show Mesopotamian influence; Aï Khanum was a Greek city; Begram‘s hoard shows strong links with Ancient Rome and India; and Tillya Tepe‘s burial treasures from the 1st century CE show a strong nomadic culture. The result is a remarkable survey of Afghanistan’s pre-Islamic heritage.

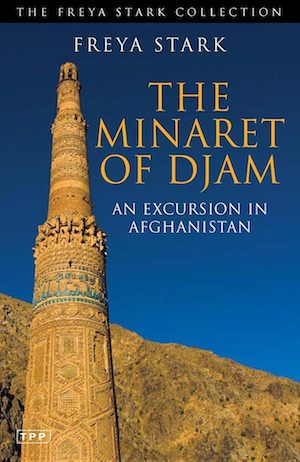

But it was in the gift shop that I made a serendipitous discovery — a travel diary by Freya Stark recounting her 1968 excursion by Land Rover straight through the mountainous heart of Afghanistan, from Kabul to Herat. “The Minaret of Djam — An Excursion in Afghanistan” had long been out of print, but was republished just a few months ago. I bought the book for two reasons: Because it is by Freya Stark, whose travel exploits are legendary; and because her destination is the Minaret of Jam (she spells it Djam) [Wikipedia], probably the most remote UNESCO World Heritage site and a long-time object of fascination for me.

But it was in the gift shop that I made a serendipitous discovery — a travel diary by Freya Stark recounting her 1968 excursion by Land Rover straight through the mountainous heart of Afghanistan, from Kabul to Herat. “The Minaret of Djam — An Excursion in Afghanistan” had long been out of print, but was republished just a few months ago. I bought the book for two reasons: Because it is by Freya Stark, whose travel exploits are legendary; and because her destination is the Minaret of Jam (she spells it Djam) [Wikipedia], probably the most remote UNESCO World Heritage site and a long-time object of fascination for me.

The Minaret of Jam was built in steep, mountainous terrain in the late 12th century, at a brief and desolate opening of the gorges on the banks of the Hari Rud river. At 65 meters, it is still today the world’s second-tallest brick minaret, behind the 73-meter tall Qutb Minar in New Delhi, which is believed to have been inspired by the one in Jam and built specifically to surpass it. Both minarets were built by the Ghurid empire, and historians now suspect the Minaret of Jam is the only structure left standing at the location of Firuzkuh, or Turquoise Mountain, the fabled Ghurid summer capital destroyed by the Mongols in 1222 and lost to us ever since.

In an authoritative report on recent excavations at the Minaret of Jam in search of evidence tying it to Firuzkuh, David Thomas recounts how the wider world rediscovered this architectural gem:

In 1886, [Colonel Sir Thomas Holdich, the Superintendent of Frontier Surveys in British India,] published reports of a tall tower in central Afghanistan but it was not until 1943 that the minaret of Jam was ‘discovered’ by S. Abdullah Malikyar, the Governor of Herat, and A. Ali Kohzad published a report on it in Dari. A report in English followed in 1952 but the magnificent tower only received world attention in 1959, when Maricq announced the discovery in The Illustrated London News and suggested that its location was ancient Firuzkuh.

Nine years later, at the age of 75, Freya Stark set out westward from Kabul to see this minaret for herself. She and a few other seasoned travelers managed to drive their Land Rover Series IIA straight through this central massif, negotiating mountain passes, fjords and barely-there tracks to reach the minaret, and thereafter Herat.

Although there was very little road infrastructure then, the 1960s and 70s provided a rare window of opportunity for unfettered travel in Afghanistan — Herat and Kabul were major destinations along the Hippie trail. Stark’s encounters with Afghans on her excursion are wholly positive, with easy hospitality provided throughout. (It perhaps helps that she spoke Farsi, of which Afghans speak the Dari dialect). There is no inkling of the coming Soviet invasion in 1979, of the insurgencies of the Mujahideen and the Taliban, Al Qaeda’s presence, and finally, the NATO invasion in 2001.

As a counterpoint to Stark, it is worth reading Rory Stewart’s modern classic, “The Places in Between“. Stewart speaks Dari and is an Afghanistan expert, and yet his quest — to walk from Herat to Kabul via Jam in January 2002, through Taliban-controlled territory a few months after the NATO invasion — is brave bordering on the foolhardy. The landscapes he travels through are those which Stark visited 33 years earlier, but his descriptions above all convey desolation, desperation and a turning inward. Remarkably, he is often received hospitably on his trek.

Stark is generous with the minutiae of her trip. She records dates, places and distances, and offers up detailed descriptions of the landscape. For example:

A higher downland spread just above. A man who came to squat beside us while we ate, with a three-cornered Mongolian face and eyes as light as the mountain sky, told us that their center there is called Bâd-Asya, or Windmill; when we climbed to it we found three shops for a bazaar and a solidly built granary like those that Hadrian left along the Turkish coast for his armies, with the same government look about it though in a smaller way. A shambling lorry trundled off down an unlikely track, and half a dozen people sitting at leisure to watch it gave a city touch, since agricultural leisure never begins in the morning. The country to the south descended in slopes of light or shadow towards clefts that led to Ghazni or the Kabul valley far away. […]

We drove on, over a wide and lovely movement of heights, from one corn basin to another, jade-green and translucent in their own depth of shadow, and slung as if suspended between fox-coloured slopes. The dust-road rounded them with edges vague as smoke, transitory and perpetual as the centuries of forgotten hooves that had sodden and bruised it into the background of its hills; and suddenly, without any preparation, we found ourselves on the brow of a precipice that looked down on Helmand [river] escaping from its gorges. The river and a tributary met there, spitting white water and twisting like snakes surprised, and continued along an easier but still narrow valley journey, where a bridge at the bottom and the opposite zig-zags showed our way. [p.49]

Reading such passages, I began to suspect there might be sufficient information here to reconstruct her trip cartographically, using tools that the inhabitants of 1968 could not even imagine: Google Earth and geonames.org. It proved possible, but not easy. There were two main challenges:

First, in many places, the roads visible in Google Earth today had clearly not yet been built in 1968, so on several occasions we find Stark’s route veering away from the road which seems obvious to follow today. In the passage above, for example, they are on a track in the southern higher reaches of the Helmand river basin, because in 1968 there is no passable road directly beside the river. Today, there is.

Second, there is no common toponomy — Stark transliterates the names she hears in Dari from locals in one way, her maps transliterate them in another, and geonames.org does so in several more ways. (Google Earth’s own gazetteer is not usable in this particular region, with the few locations mentioned often off by many kilometers.) Fortunately, geonames.org has two very powerful tools: It has a KML network link for Google Earth that shows you its entries for your current view; and its website has a very robust fuzzy search function, with alternate names that more often than not nail what you’re looking for.

In the passage above, Stark hears the name “Bâd-Asya”, and writes it down according to her own rules for transliteration. geonames.org, however, lists “Sar-e Badah Siah”, where “Sar-e” denotes some kind of populated place. Sometimes, then, finding a location mentioned in the book took some creative reading of the candidates offered up by the network link as I roamed around the general area Stark would have traveled through.

Other techniques came in handy as well. Google Earth’s 3D perspective is especially useful in hilly landscapes like these, because it becomes s much easier to get a feel of the land, finding watersheds and mountain passes and seeing which valleys are flat enough for passage.

User-generated content was another useful tool for triangulating a location name. For example, on the first night, they camp at the edge of the Helmand river:

A hamlet of four houses was the centre of this small world, tucked at the foot of a promontory of rock and shale: Dané-Ausela they called it, but the map suggests Kizil-Bashi (Red-head) and the traveller can choose — as indeed he can with most of the smaller eastern names: the seldom agree with the maps, which never agree with each other.

Geonames was coming up empty, but then the Google Earth default photo layer provided the crucial hint, with a couple of rare Panoramio photos labeled “Dane-Awdela”. This in turn brought attention to a nearby Geonames place name: “Dahan-e ‘Abdullah“, a corroboration which in my mind confirms this as the place. There is no other name nearby remotely like it.

With techniques like this, I was able to map out the daily route of Stark’s expedition, from her departure in Kabul on August 8, 1968 to her arrival 8 days later in Herat. It’s available for download as a KMZ file, to be opened in Google Earth. The best way to use this tool is to buy the book and keep Google Earth alongside you as you read it. Doing so adds a whole new dimension to her travelogue.

I’m very confident about the accuracy of most of the map. In some parts, there is ambivalence about which specific route she took across a region, so I draw alternate paths. The route I am least sure about is the one she took on August 14. It begins and ends in the right places, but the path in between that fits with most of the evidence does not pass a certain nearby village she says they drove by. However, Stark refers to the village noncommittally as “a place which seems to be called Margha on the map”, so it’s possible that in this instance, she read the map wrong. In any case, the KMZ file comes with the Geonames network link included, so you can easily build your own theories. Any corrections or suggestions are welcome.

The above KMZ file contains some further “bonus” content. At the start of her book, Stark describes a visit to he Buddhas of Bamian, and I’ve marked up the relevant place names there. (Stark calls them “the huge, and lets face it, ugly Buddhas”, but is spared any regret she might have felt at her choice of words when the Taliban demolish the Buddhas in 2001 — She died in 1993, a centenarian.) She also mentions the northern cities of Balkh, Tashkurgan and Kunduz, and a series of passes. I’ve marked those up as well.

Finally, I have also added the locations of the sites whose treasures are in the Afghanistan exhibition currently on show in London. Tepe Fullol in particular is an obscure, out-of-the-way site.

I will admit that I have on occasion lurked on Lonely Planet’s Thorn Tree travel forum, looking for safety information on the Kabul-Jam-Herat trip. The advice varies by year. In 2007, it was deemed safe to travel from Herat to Jam. In 2010, not so much. Places like Panjau also seem to have changed in character. When Stark passed by it was “a miniature village-town with some signs of coquetry about it”. By 2010, one seasoned traveler described it as “a s**t-hole filled with yucking yokels, only worth getting out of.”

Let’s hope Afghanistan will be over its troubles by 2018, the 50th anniversary of Freya Stark’s excursion. Perhaps then would be an opportune time to retrace her trip. The research has been done. Who’s in?

Recent reads: Libya, World Heritage Network, Japan

IMINT & Analysis: Libyan NFZ: The SAM Threat

Sean O’Connor over at IMINT & Analysis has a thorough exposition of the Libyan anti-aircraft surface-to-air missile bases that the US and UK Tomahawk missiles have likely been targeting.

Separately, IMINT & Analysis also updates the available intelligence on the newest class of Chinese submarines, spotting one in the North Sea Fleet in the latest imagery available on Google Earth. The submarine in question is moored outside the “secret underground submarine base” much-blogged here on previous occasions.

Global Heritage Fund: Global Heritage Network

The Global Heritage Fund, a non-profit dedicated to preserving the world’s cultural heritage, has just launched Global Heritage Network, a very impressive browser-based augmented Google Earth application that overlays all manner of geospatial information over threatened world cultural sites. Included in the entry for Kashgar are some of the photos I took in August 2010 (blogged here). I found this web app to be surprisingly usable and useful — often, these kinds of projects don’t work beyond being a technology demonstration. (To get a URL link for a view of a specific location, perform a search for it and click on the resulting link.)

Nikon Rumors: Satellite images of Nikon Sendai plant before and after earthquake

Goole Earth and Maps has been used in many ways to document the the earthquakes and the tsunami’s devastating effects in Japan this past week (See Google Lat Long Blog, Japan Quake Map). One more unusual use of the post-tsunami satellite imagery was by Nikon Rumors, which was able to confirm a lack of damage to one of the main Nikon factories, located in Sendai. No doubt equity analysts the world over are doing the same so as to adjust their portfolios. One thing to remember when looking at the before and after imagery: It can only show damage to physical capital, not human capital — it won’t tell if or how many Nikon plant workers, living nearby, perished.

Recent reads: Dutch-German border dispute, Israel Street View

Here are some interesting stories that have popped up on the radar screen these past few weeks:

Strange Maps (Mar 1): 504 – Bordering on Bizarre: Google Maps Fail in Dollart Bay

You’d be forgiven for thinking that border disputes are not something that neighboring European Union members get embroiled in. You’d be wrong: The Netherlands and Germany diverge on where the maritime border between them lies. One thing both sides agree on, however: The way Google Maps currently depicts the maritime border is wrong:

It gives the Netherlands all of the maritime territory in question, including the harbor of Emden, a German town. The error is only visible in Google Maps. Google Earth (sensibly?) doesn’t try to depict maritime borders. Emden city council, meanwhile, has been trying to alert Google for the past year, clearly without success.

Associated Press (Feb 21): Google Street View raises Israeli security fears

Jerusalem Post (Feb 20): In Israel Google Street View needs serious thought

As the Associated Press reports, Israel’s government would like for Google Street View to come to Israel, but first wants to work with Google to minimize security risks. The Jerusalem Posts column proposes how this collaboration might work, but the suggestions are a bit… bizarre?

Keeping the data in Israel is the only way to ensure the Israeli courts can order enforcement. This may be a good first step. Israel also has a responsibility to act in the Interests of its people and of the Jewish people more generally. In light of that, Israel may also request further unrelated guarantees from Google, such as an undertaking to cooperate more fully with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in the fight against Antisemitism.

First, if Google had to keep the only copy of each country’s geospatial dataset in that country, there would be no Google Street View or Google Earth. The data resides in redundant server farms around the world. If Israel wants to have a legal grip on Google, I suggest looking in the Tel Aviv phone book for their offices.

Second, I’m sure that Google is against anti-semitism, as they are against racism and homophobia, but this is an issue wholly unrelated to Google Street View, as the JPost op-ed piece concedes. Then why connect them? Holding up regulatory approval in one matter until a company concedes on an unrelated matter is called being held to ransom.

ISIS Reports (Feb 23): Satellite Image Shows Suspected Uranium Conversion Plant in Syria

Remember that North-Korea designed nuclear reactor under construction in Syria which Israel bombed in September 2007? Germany’s Sueddeutsche Zeitung has now identified a further site that was related to the reactor, and whose purpose at the time Syria now seems to want to hide. ISIS has now commissioned imagery to further analyze this site.

Google Lat Long Blog (Feb 15): Act Locally in Sudan with New Imagery & Maps

Google releases new imagery for soon-to-be newly independent South Sudan, and urges the creation of local mapping communities in both Sudans.

Google Earth and the Middle East

The Middle East is where Google Earth has perhaps had the deepest geopolitical impact since its introduction in June 2005. In these 5+ years, the wide availability of high resolution imagery of the region to anyone with an internet connection has caused a slew of governments to fret, and not just the Arab dictatorships — Israel and the UK have also worried, as we’ll see.

In his New York Times op-ed column on Wednesday, Thomas Friedman calls Google Earth one of the “not-so-obvious forces” behind the revolutionary fervor currently gripping the Middle East. The reason cited by Friedman: in 2006, Google made visible the opulent palaces of Bahrain’s ruling family to a populace in the grip of a housing shortage. Outrage ensued, albeit online. The inequalities were simply too striking.

Friedman doesn’t mention the most interesting aspect of this episode: The story only gained traction after Bahrain’s embarrassed sheiks, in a typically autocratic move, ordered the country’s ISPs to block access to Google Earth’s imagery, in August 2006. (I wrote about the story here and here). The response was a perfect example of the Streisand effect: Suddenly, everybody in Bahrain was curious about what they weren’t allowed to see. One enterprising activist took screenshots of the imagery (still available to everyone outside bahrain) and turned it into a PDF, which became an instant email hit. (You can still download it from Ogle Earth’s server via this story). After three days, Bahrain’s rulers were humiliated into restoring access to Google Earth.

This is just one anecdote of many that Friedman could have used — but for some reason, it is the Bahrain story that has recently been doing the rounds again, for example in the just-launched The Daily for iPad.

What about the others? Here’s a quick tour of Google Earth’s uses in the Middle East this past half decade.

Tunisia: You know what Google bombing is. In 2008, activists did something similar in Google Earth, “Google Earth bombing” the palace of (now ex-) president Ben Ali with YouTube testimonies of political prisoners. Anyone who zoomed in on his palace would see geopositioned YouTube icons, each one ready to play a video detailing the nastiness of his regime.

Sudan: Sudan has had a rather schizophrenic relationship with Google Earth. For a long time, Google Earth was not available for download in Sudan — not because Sudan’s government blocked it, but because US export restrictions made it illegal for Google to offer it. At the same time, recent satellite imagery of burned villages in Darfur as the Sudanese regime waged war on its own citizens, highlighted by Google through new default layers, brought that conflict home in new ways to everyone except the Sudanese.

Iraq: Iraq is one of the few parts of the globe not to regularly receive new imagery in Google Earth. (Afghanistan is another). The reason for this dates back to early in 2007, when British troops in Basra said they had found CDs with screen dumps of Google Earth imagery of their camps in the local market, arguing that insurgents could use this to fine-tune their mortar attacks. Never mind that the imagery was over two years old, and that it was available for sale elsewhere: In the only proven case of active censoring by Google to date, the company removed all post-war imagery in Iraq, replacing it with older imagery. Eventually, the imagery in question was removed from sale by other vendors as well.

Yemen: In Yemen, using Google Earth to help secessionist rebels got one guy 10 years in jail. But he wasn’t even the first to try.

Iran: Never mind that until a few weeks ago, Google Earth was not available in Iran (US export restrictions, again): Some Iranians have long been upset that the Persian Gulf is labeled not just with that name in Google Earth… but also as the Arabian Gulf, which is the name taught in schools in the UAE and the rest of the non-Persian Gulf states. Google using both place names, with an explanation why, simply didn’t cut it for these Iranians, and the result was a massive online petition to demand that Google remove the offending “Arabian Gulf” moniker. When I last checked, 1,242,141 people had signed the petition. Google’s response: A detailed naming policy, which unsurprisingly did not appease Iran’s foreign ministry.

Imagery in Google Earth has also been used to monitor and publicize Iran’s nuclear program. (See here, here, here, here and here.)

Saudi Arabia: A Saudi researcher caused a stir when he used Google Earth to check whether some of Saudi Arabia’s main mosques were accurately aligned in the direction of the Qibla, i.e. Mecca, and found that some were wanting.

Syria: Satellite imagery in Google Earth has been used by various actors as publicly available evidence to convince the public that Syria’s government was up to no good, such as building a secret nuclear power plant with North Korean help (now bombed by Israel), or allegedly letting Hezbollah hoard Scud missiles.

Israel: Google Earth’s user-contributed layers have been used by sympathizers of the Palestinian cause to influence the narrative of the history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict: In 2006, an exhaustive annotated list of Israeli settlements in the West Bank was added to the Google Earth Community layer; in 2008, another layer purported to show Arab villages in Israel that had been ethnically cleansed during the war that followed Israel’s declaration of independence. One town, Kiryat Yam, was apparently added in error to the list, which led it to sue Google for slander, while other pro-Israel interest groups accused Google of anti-Israel bias (though they did so on ungrounded assumptions.)

Israel has long had special treatment when it comes to the resolution of publicly available satellite imagery of its territory. Due to an American law, the Kyl-Bingaman Amendment, US imagery providers cannot currently sell imagery of Israel that is better than 2 meters per pixel in resolution, which is artificially lowered from the maximum resolution available by the same satellite over the rest of the world. Israel is the only country that has this exemption. Not even US nuclear power plants have this kind of legal cover.

One oft-cited reason for this need for “protection”: Stories showing militants bragging about how they use Google Earth to plan their attacks. The only problem is, 2m-resolution imagery is plenty accurate if you are trying to plan a rocket launch out of Gaza.

In sum, Google Earth has had quite an impact on the region. My own guess is that geographic awareness of the region has greatly improved, not just globally, but by Arabs themselves. On the Yemeni island of Socotra in February 2009, I walked into the only internet café in a 400km radius. The first screen I saw had Google Earth’s familiar globe on it, with rapt teenagers steering it, doing their homework. These kids’ perspectives of the world, so radically different from their parents, are one major factor driving the current revolutions in the Arab world.

links for 2011-02-09

-

Position data for a live helicopter video image is used to generate labels in real time, which are then superimposed onto the video. With enough such helicopters in the air, you could paint a live map of a region:-) Check out the linked video too.