On November 12, a powerful explosion ripped through an Iranian missile base on the outskirts of the town of Bīdgeneh, 40 km west of Tehran. As the Guardian reported soon after, among the dead at the base was the architect of Iran’s missile program, Major General Hassan Moghaddam. There has been heavy media speculation the explosion might have been the result of a covert operation by Israel’s Mossad.

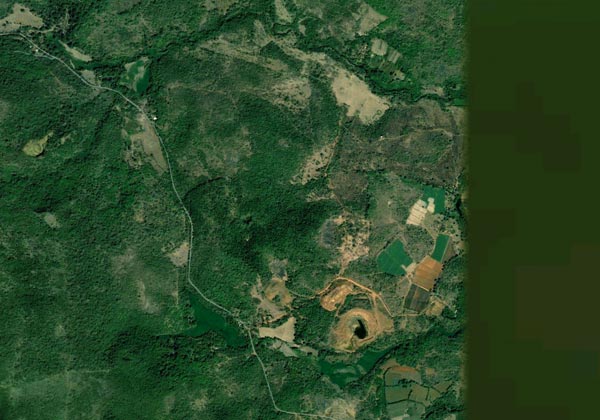

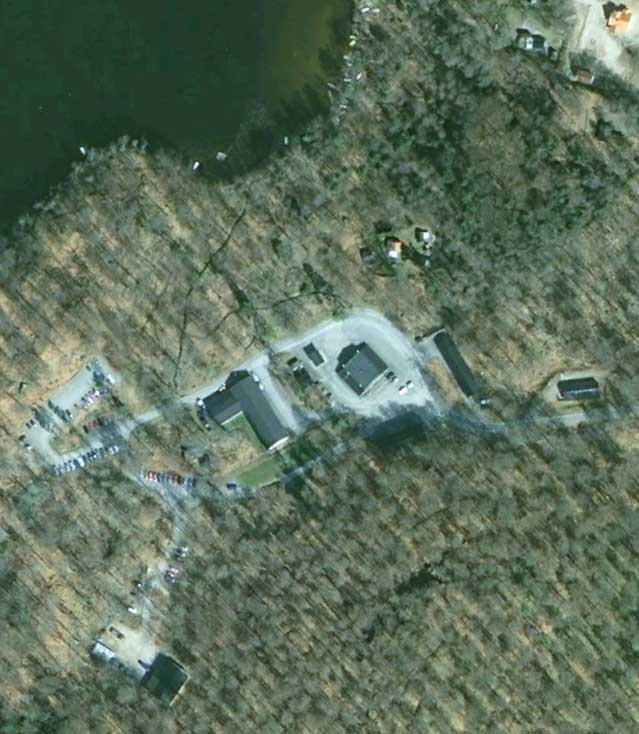

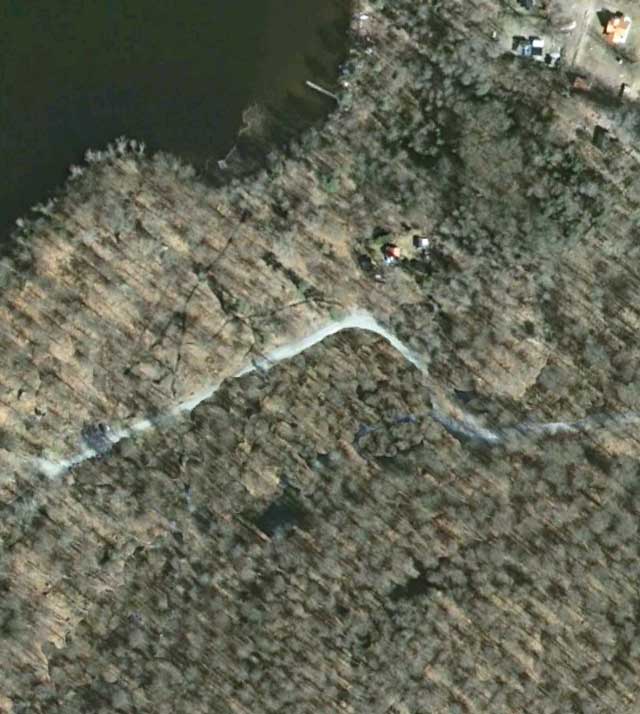

Post-explosion satellite imagery has now become available that shows the extent of the destruction. Commissioned by the Institute for Science and International Security (ISIS), the imagery was taken on November 22, 2011. ISIS Senior Research Analyst Paul Brannan has published the annotated image along with the most recent available imagery from before the explosion, taken September 9, 2011. He adds:

ISIS learned that the blast occurred as Iran had achieved a major milestone in the development of a new missile. Iran was apparently performing a volatile procedure involving a missile engine at the site when the blast occurred.

You can’t tell from the imagery if sabotage caused the explosion, but you can tell the damage was extensive, wiping out most structures at the base. The NYT elicits more commentary from Paul Brannan in an interview.

Because ISIS’s web post and accompanying PDF used lower-resolution versions of the Nov 22 image, I asked ISIS for the original high-resolution image, to overlay on Google Earth. The September 9 imagery is already in Google Earth’s base layer, so it was just a matter of overlaying the one new image. Here is the resulting KMZ file, containing the high-resolution original, ready to open in Google Earth.

In Google Earth 6 and above, remember to click on the opacity button in the sidebar and then play with the opacity slider to switch between the before- and after- imagery. For reference, the sports court at the base is 30×15 meters, about the size of a basketball court.

P.S. On November 28, an new explosion ripped through what appears to be a uranium conversion plant near Isfahan, rattling windows in the city. Speculation is mounting (some based on intelligence sources) that Iran’s nuclear and missile programs are being systematically sabotaged or attacked. In 2010, the Stuxnet worm caused heavy damage to the uranium enrichment facility at Natanz.

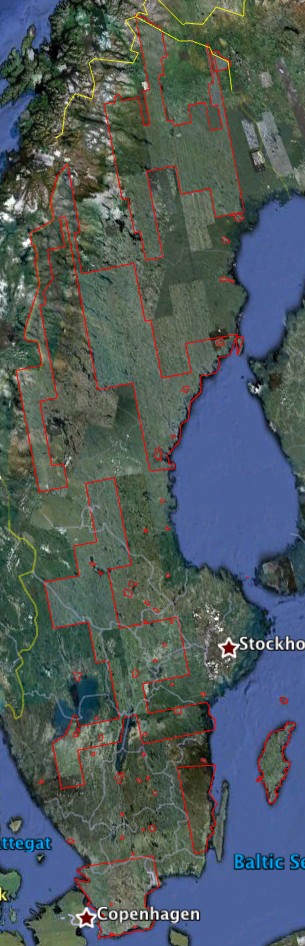

Just a quick heads up for Swedes and/or power users of Google Earth: I noticed via the

Just a quick heads up for Swedes and/or power users of Google Earth: I noticed via the