The eastern third of the border between Nicaragua and Costa Rica is determined by the course of the Río San Juan as it wends its way eastward towards the Caribbean Sea. In the final 20-odd kilometers, the river splits into two, with the border following the smaller, northernmost strand. (The southern strand is considered to be a different river, the Río Colorado.) These two rivers delineate the delta island Isla Calero, Costa Rica’s largest.

The mutual border was determined by the Cañas-Jerez Treaty of Limits in 1858, after a series of military escapades between the two countries motivated in part by the Rio San Juan being a candidate for a trans-isthmus canal. According to the terms of the treaty, the south bank of the river is Costa Rican territory but the river itself is Nicaraguan. Costa Rica has the right to use the river for commerce.

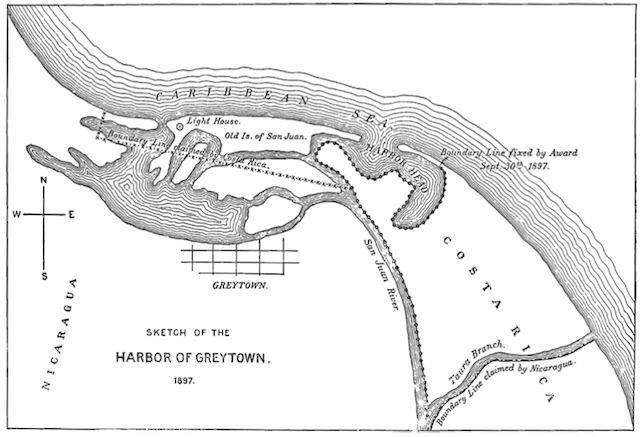

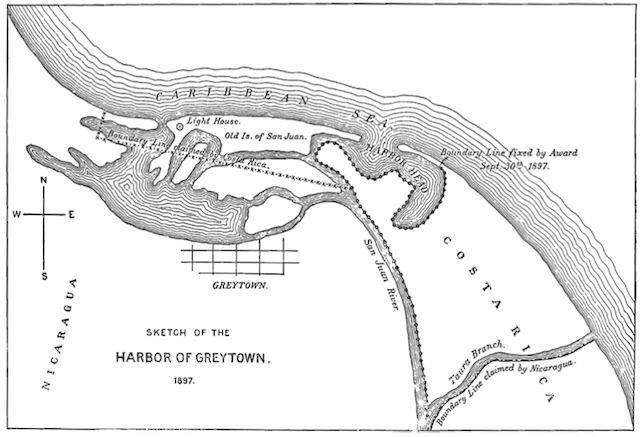

Differing interpretations of the treaty led US president Grover Cleveland to arbitrate the continuing dispute, ruling in 1888 (in the “Laudo Cleveland” or Cleveland Award (PDF)) that Costa Rica did not have the right to patrol the river with military ships. This same document also resolved that Punta de Castilla, “at the mouth of the San Juan River”, is where the border runs into the sea. In 1897, a more technical arbitration (PDF) by E.P. Alexander (at the behest of Cleveland) delineated the border with greater precision near the coast:

The dispute flared up again this century, with Costa Rica in 2005 complaining to the International Court of Justice that Nicaragua was unfairly restricting access to the river. The Court’s ruling, delivered in 2009, was Solomonic: It ruled that Costa Rica cannot resupply its armed police border posts by river, but also that Nicaragua cannot demand visas from Costa Rican tourists traveling along the river.

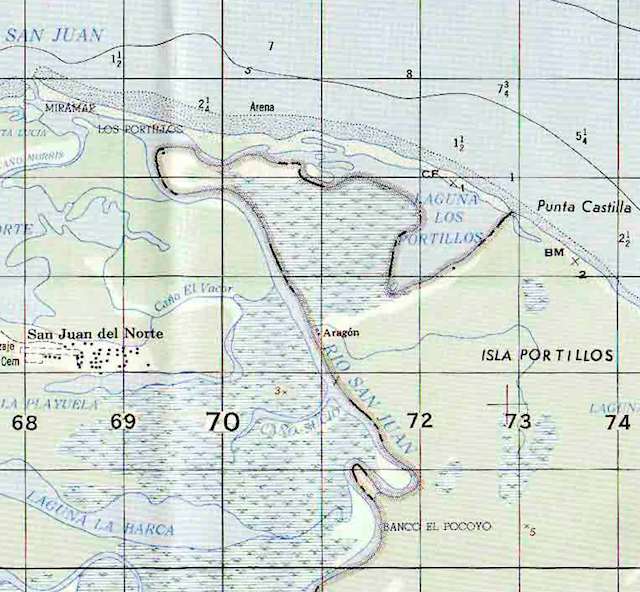

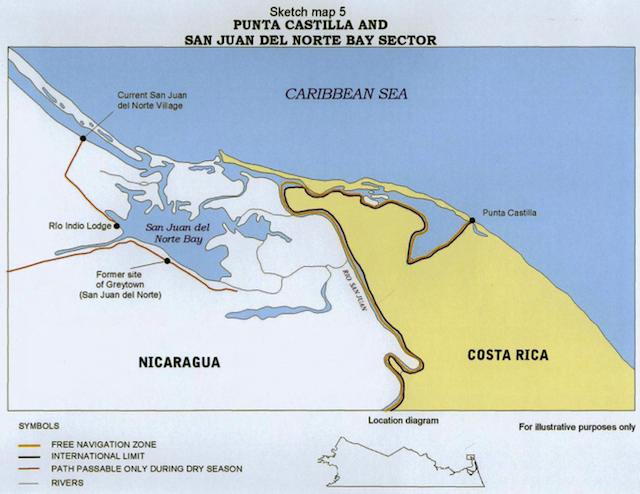

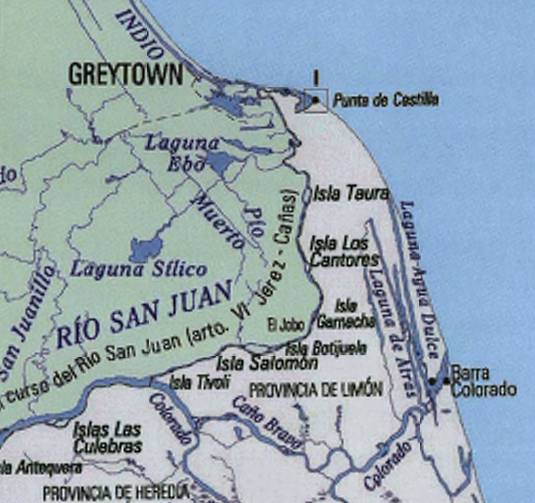

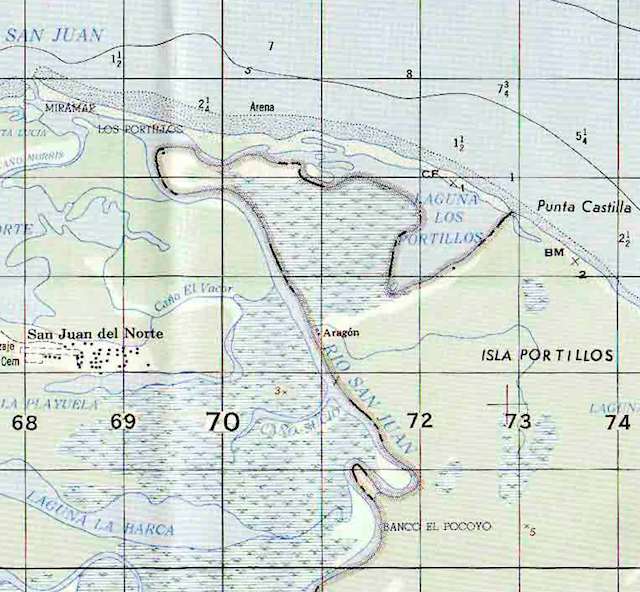

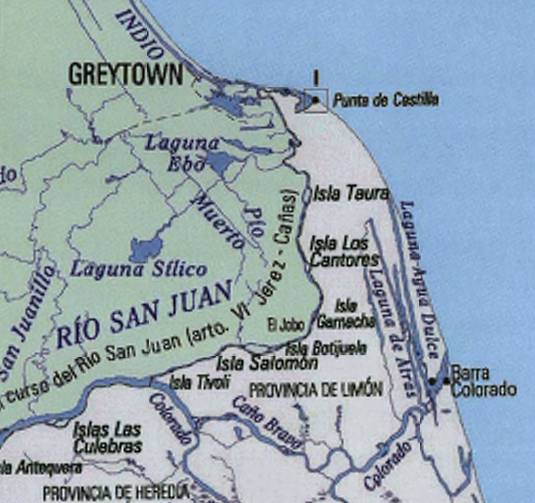

You’d think this ruling would end any possibility of further border disputes. In any case, the official maps of both Nicaragua and Costa Rica do not dispute the border:

Section of Nicaraguan national map

Section of Costa Rica’s national map

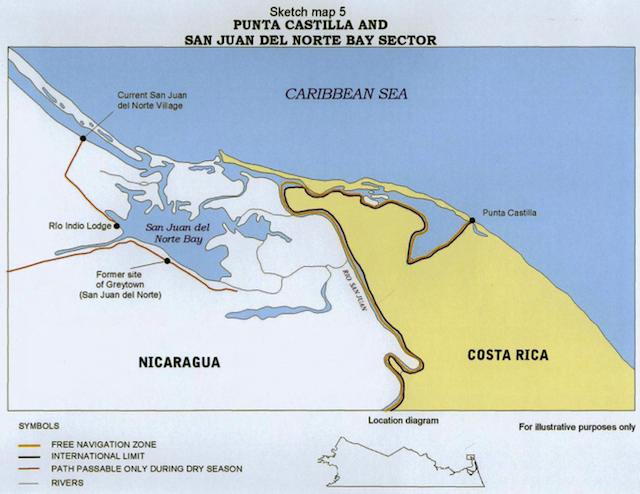

The maps delivered by both countries to the ICJ as recently as 2006-2007 are not in dispute either:

Map provided by Costa Rica to the ICJ

Map provided by Nicaragua to the ICJ

Nevertheless, during the second half of October 2010, Nicaraguan troops set up camp on Isla Calero, on the Costa Rican bank of the San Juan river just a few kilometers from where it reaches the Caribbean, raised the Nicaraguan flag, and then began tree clearing and dredging operations which are still ongoing. Their aim, so it seems, is to clear a channel that reflects what Nicaragua believes might have been the course of the river back in the 1850s.

How to justify such an apparently blatant incursion? The clearest explanation I’ve found of the Nicaraguan position comes directly from Nicaraguan President Daniel Ortega himself, as reported in the Tico Times:

Ortega said the Costa Rica border has been steadily encroaching northward for hundreds of years, as the San Juan River delta slowly dries out. However, he said, even though the historic river mouth has dried, it is still Nicaraguan territory.

“In the 1600s and 1700s, the river covered an enormous amount of territory at its delta,” Ortega said. “And as the zone has dried, the river has moved and (Costa Rica) has continued to advance and take possession of terrain that doesn’t belong to it. The way things are going, if the San Juan River continues to move north and join with the Río Grande of Matagalpa (in the northern zone), that’s how far (Costa Rica) would claim its territory extended.”

Ortega stressed that according to the July 2009 resolution from the International Court of Justice at The Hague, Nicaragua has the right to recuperate the historic delta of the San Juan River that existed more than 150 years ago.

“Nicaragua has the right to dredge the San Juan River to recover the flow of waters that existed in 1858, even if that affects the flow of water of other current recipients, such as the Colorado River,” Ortega said, reading from last year’s resolution for The Hague.

The section of the ICJ ruling Ortega refers to is worth quoting at length. It doesn’t concern the main question of the ruling, but regards an additional declaration that Nicaragua wanted the ICJ to adopt in its ruling:

153. Nicaragua adds a further submission. It requests the Court “to make a formal declaration on the issues raised by Nicaragua in Section II of Chapter VII of her Counter-Memorial, [and] in Section I, Chapter VI of her Rejoinder”.

The declaration requested is the following:

“[(i) … (iv) redacted]

(v) Nicaragua has the right to dredge the San Juan in order to return the flow of water to that obtaining in 1858 even if this affects the flow of water to other present day recipients of this flow such as the Colorado River.”

[…]

155. As for the fifth point to be addressed in the requested “declaration”, on the assumption that it is in the nature of a counter-claim, Costa Rica has cast doubt on its admissibility, arguing that it is not “directly connected” with the subject-matter of Costa Rica’s claim, within the meaning of Article 80 of the Rules of Court. The same issue could arise in respect of the third point.

In any event it suffices for the Court to observe that the two questions thus raised were settled in the decision made in the Cleveland Award. It was determined in paragraphs 4 to 6 of the third clause of the Award that Costa Rica is not bound to share in the expenses necessary to improve navigation on the San Juan river and that Nicaragua may execute such works of improvement as it deems suitable, provided that such works do not seriously impair navigation on tributaries of the San Juan belonging to Costa Rica.

As Nicaragua has offered no explanation why the Award does not suffice to make clear the Parties’ rights and obligations in respect of these matters, its claim in this regard must be rejected.

Clearly, the Court rejected Nicaragua’s request to add its proposed text to the ruling. But it is also now clear that Nicaragua has chosen to interpret the Court’s reaffirmation of the Cleveland Award as a legal go-ahead to clear and dredge those channels it claims were commercial waterways in 1858, even if these subsequently silted up as the course of the San Juan river shifted over the past 150 years.

Costa Rica has complained to the Organization of American States, but Nicaragua argues that the only body fit to rule on the issues is the ICJ. Since another ruling from that court would take approximately 3 years from start to finish, presumably this gives Nicaragua enough time to finish whatever waterworks it deems necessary. Considering that Costa Rica abolished its military in 1948, it is not really in a position to prevent Nicaragua from acting. Meanwhile, Nicaraguan parliamentarians have vowed to travel to Isla Calero on November 10, to “reaffirm the defense of national territory.”

Where does Google Maps figure in all this? Opportunistically, it turns out. As long ago as October 22, 2010, Edén Pastora, the nationally famous Sandinista ex-revolutionary and now Nicaragua’s director of dredging on the Río San Juan, was arguing patriotically (translation) that the region is a no man’s land because the San Juan has changed course since the 19th century, when the Cleveland Award determined the border. By November 2, 2010, he had discovered that Google Maps’s border gives Nicaragua the top part of Isla Calero, and subsequently used this to justify the troop encampment on the island (translation). This prompted Costa Rica’s foreign ministry to contact Google, which in turn scrambled to check with the source of its data (the US State Department). Google has now said that the current Google Maps border for the area is wrong and that it will be updated as soon as possible.

Google’s current incorrect border

Given all this information, we can conclude that the narrative currently dominating the internet is wrong: Nicaragua did not mistakenly enter Costa Rican territory because it relied on Google Maps. Ortega’s justification for Nicaragua’s actions appeal to documents from the 19th century; Pastora’s mention of Google Maps is just a taunt.

A couple of loose threads remain. First, Bing Maps doesn’t come off nearly as well as Search Engine Land’s post would have you believe. A cursory glance shows that Bing’s border does not accurately follow the course of Río San Juan. For a good 10km stretch, Bing actually gives Nicaragua both banks of the river, but at the same time grants several coastal islands to Costa Rica. This is because the dataset is not detailed enough to withstand a close-up.

The US State Department’s admittedly faulty border, as depicted in Google Maps, is more of a puzzle. I first thought it might indeed have been an old dataset from the 1850s or 1880s, showing the course of the Río San Juan back then (as Pastora would have us believe), but I now think the dataset has to be modern but corrupted. That’s because Google’s border shows the distinct S bend in the river’s final few kilometers — an S bend which did not exist when E.P. Alexander drew his survey maps in 1897.

Finally, a Costa Rican TV program on the issue (part 1, part 2) shows Nicaragua’s new claim line, but this line matches neither Google Maps’s border nor the border as surveyed by Alexander.

Screen grab from TV show showing where Nicaragua purports Alexander mapped the course of the Río San Juan. The screencap also shows the position of the dredger (bottom). Below, how Alexander actually drew the course of the river (via Google Lat-Long Blog).

Update 17:28 UTC: Below is a better version of the new Nicaraguan claim line: an infographic from Nicaragua’s La Prensa. Note the clear appeal to E.P. Alexander’s survey map, but this appears to be contradicted by Alexander’s actual maps, reproduced above. h/t @EscalaNatural

Current incorrect border in Google Earth, showing the S-shaped river course.

What Nicaragua has yet to produce is an antique map showing the course of the Río San Juan in the 1800s along the route it now claims as the new border. Even if it does, convincing the ICJ of this claim line’s legitimacy will be a tall order, considering how both countries have for well over a century mapped their mutual border according to the shifting banks of the Río San Juan. Nicaragua’s plan to artificially change the course of the river — and thus the border — by dredging and clearing gets points for originality. I just don’t think it will fly with anyone who is not already a Nicaraguan nationalist.